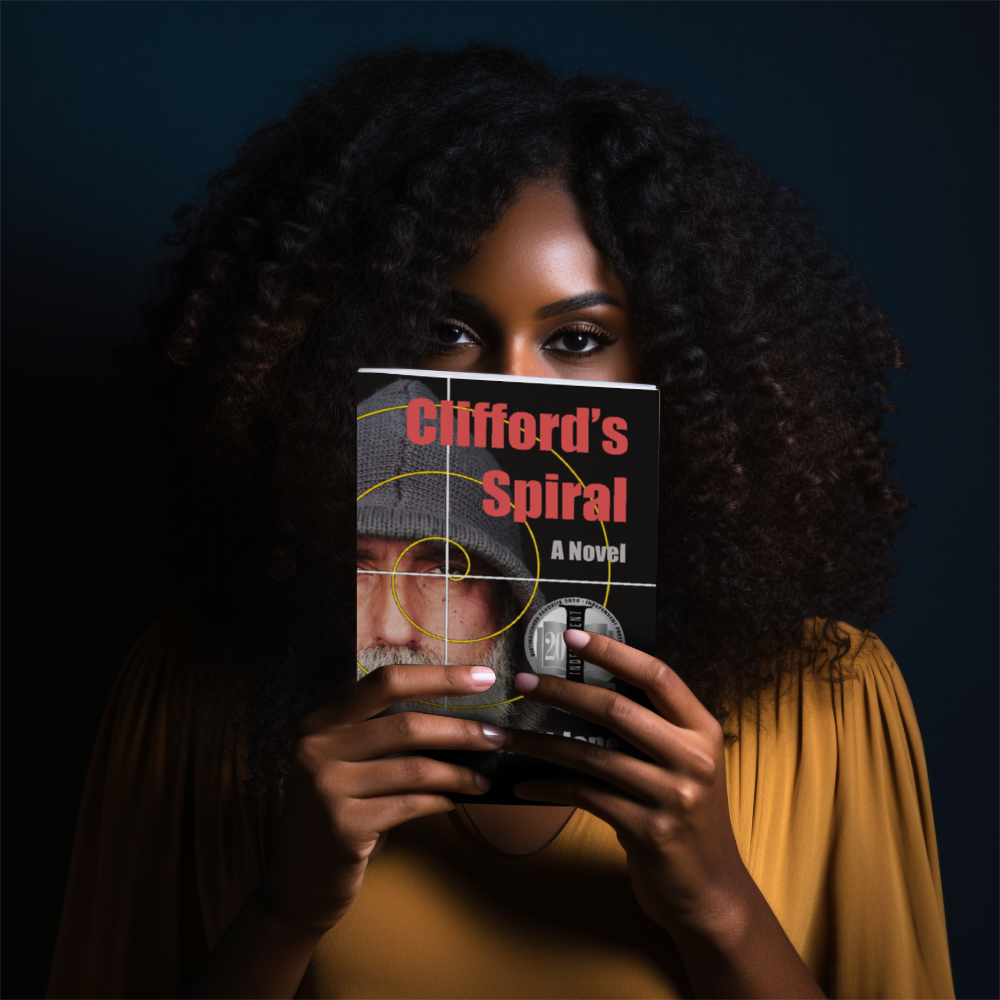

Clifford's Spiral: Chapter 6

Should he worry about falling in love with his caregiver?

Chapters are serialized here for paid subscribers.

About This Novel

In Clifford's Spiral, the stroke survivor’s past is blurry, and his memories are in pieces. He asks himself:

Who was Clifford Olmstead Klovis?

Stroke sufferer Clifford Klovis tries to piece together the colorful fragments of his memories. Meanwhile, who owned the lovely hands that were touching him?

Chapter 6

Clifford’s eyelids floated closed, not because he was drifting off to sleep but because he’d given into bliss. Nurse Myra was running the heel of her right thumb with deep pressure repeatedly along his inner left thigh from knee to groin, tracing the route of his femoral artery. She’d just finished working on his calf with both thumbs, after having used acupressure reflexology on the soles of his feet. He marveled at her confident skill and the strength in her hands. When she’d been working on his feet, he’d wished he’d studied some reflexology himself. If he had, the precise points where he’d felt brief, excruciating pain would have given him clues about what was going on with his internal organs. He didn’t think he was sick — any more than the consequences of having had a stroke. His appetite was normal if not sometimes voracious, his digestion proceeded relentlessly, and he hadn’t noted any congestion in his respiratory tract. Given this lack of symptomatology, how had Myra been able to find those nasty pain points? Was his liver going bad? Tumors growing in his colon? Kidneys about to fail? Undoubtedly, any of those conditions would present other, more ominous, symptoms.

Wouldn’t they? But, come to think of it, why should I worry? A second stroke would probably finish me off, and there are undoubtedly more painful ways to go.

It’s like what his internist told him about prostate cancer — yes, it’s serious and potentially fatal — but it usually progresses so slowly that something else will get you first. None of his doctors had ever told him he actually had prostate cancer, so he wondered why this guy would have told him such a thing. These days they weren’t allowed to hint, much less withhold information. If you had something, they were supposed to tell you — describing your condition in no uncertain terms even if they were sure you’d rather not know. Gone were the days of letting the patient think he’d live forever until the day he felt so sick he knew he wouldn’t.

As Myra’s thumb reached the top of his inner thigh, it veered away quickly before touching his scrotum. It was a deft movement, executed at just the right place to avoid exciting him sexually.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thinking About Thinking to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.