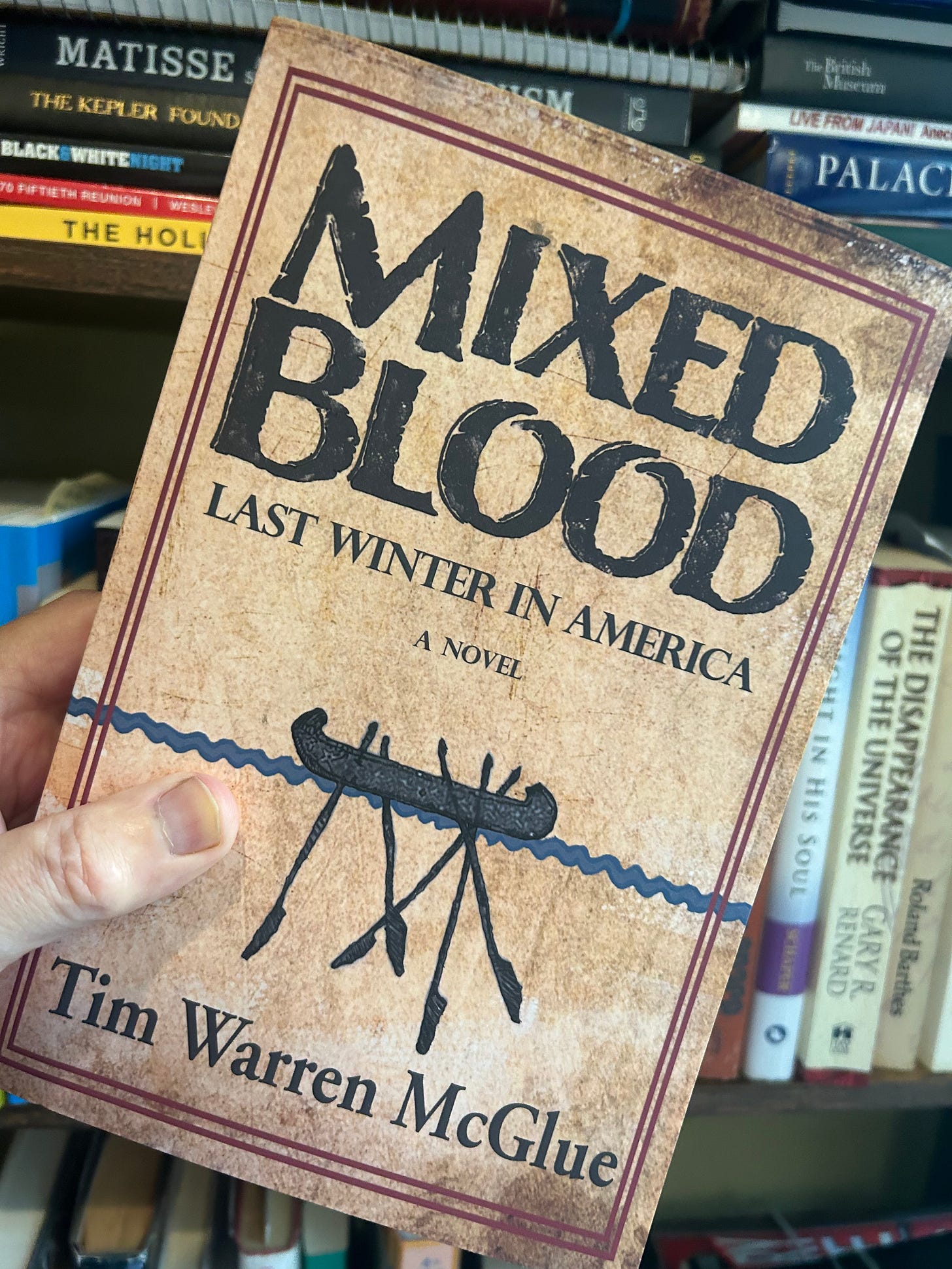

Book Review: 'Mixed Blood' by Tim Warren McGlue

Once again, historical fiction is all about today.

McGlue’s new novel recaptures his ancestor’s legacy

First, by way of introduction, I must disclose that I was Tim McGlue’s roommate in Paris during l’epoque des barricades in 1968. We weren’t activists. Our group of underclassmen from Wesleyan’s College of Letters was nominally registered at the Sorbonne, but we took classes with tutors, including Roland Barthes, who became famous as the father of semiotics. Most of that, including reasons for the student riots, was over our heads at the time. We probably thought the unrest was a protest against the war in Vietnam. Back then, Americans sometimes received an indifferent reception in France because - having recently abandoned their own stake in Indochina - the French seemed offended by the notion that U.S. troops kept trying where theirs had failed. It turned out - and I don’t remember when I learned this - that the protests were mainly a rebellion against the aristocratic track system of the University of Paris, which not only favored the wealthy but also placed them in cushy jobs after graduation.

Sound familiar?

Available in paperback and ebook from Polyverse Publications and booksellers worldwide.

Anyhow, McGlue, who hails from Indianapolis, unaccountably was wonderfully fluent in French. I’d had several years of study myself, but I could barely get a few words out. My short stature and dark features made me look like a Belgian or a Brit if the locals caught my atrocious accent. But my friend was tall and sandy-haired, sporting cowboy boots and corduroys. When they heard his mellifluous speech, amazingly, he was “un cowboy de Far West qui parle couramment!”

Ah, yes. Enough of personal history.

McGlue has thoroughly researched the life and work of his nineteenth-century forebear, William W. Warren, who grew up on the edge of the western frontier, son of an Ojibwe mother and a white trader father. As historical fiction, Mixed Blood: Last Winter in America is both earnest and ambitious - coming in at 498 pages.

Besides coping with his mixed-race parentage, Warren’s world is colored by the U.S. government's forced removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in 1850s Minnesota, as it had been occurring in the Midwest for decades.

Warren's learning both Ojibwe and English languages and embracing the traditions of both cultures cast him in the role of interpreter and mediator between the Ojibwe and the white settlers.

At the heart of the narrative lies the tragedy of Sandy Lake, a pivotal event that forces Warren to confront the harsh reality that progress, as defined by the U.S. government, must not be halted. Unfulfilled promises of food and annuities result in hundreds of Ojibwe deaths from starvation, disease, and exposure. This crisis prompts Warren to believe that safeguarding the oral traditions of his community must be his life’s mission.

The novel's crux is Warren's decision to embark on a perilous journey to collect and record the oral histories of the Ojibwe elders. His manuscript, History of the Ojibway People, becomes a beacon of hope in the face of cultural erasure. His journey to New York during a harsh winter becomes a symbolic struggle against failing health, his own laudanum addiction, and societal bigotry.

The novel masterfully describes Warren's challenges as he struggles to find his identity, race, culture, and history. Predictably, Warren's publishers reject his manuscript. White culture has no wish to hear versions of history as told by the vanquished.

Sound familiar?

The novel recounts Warren's untimely death in 1853, marking the end of a dedicated individual who strived to preserve his tribe's legacy. However, the recovery of his lost manuscript eventually completes his mission. Published in 1887, History of the Ojibway People became prominent by offering a unique perspective from the words of Ojibwe grandfathers.

The existence of Warren’s book is not a fiction contrived by McGlue to tell a story. It’s hardly surprising today to read its catalog descriptions, which point out that indigenous people may disagree with Warren’s account.

Let the debates continue!

Historical fiction is all about today. Contemporary minds look back on events through lenses colored by everything that has happened since. We might identify with our forebears, but we can only guess at their thoughts as if translating from some obscure tongue.

McGlue's narrative resonates with themes of courage, sacrifice, resilience, and the determination to preserve a unique and valuable culture.

Why should we care about history - especially the painful incidents that might make us cringe?

Anyone who thinks seriously about thinking knows the answer.

Feed your curiosity with a paid subscription to this Thinking About Thinking blog. You’ll gain access to all the content that’s here, and you’ll be helping us build our worldwide community through storytelling and self-expression.

Fun, yes, but teargas not so much. It carried everywhere, especially down into the subway. Remember, we were sophomores. The university referred to this foreign-study program and the ungraded College of Letters major as "a gamble on maturity."

Damian, Your "Get the Cheese" is in the queue, rather like a plane circling LAX, but it will glide in one of these days soon.